A new book has unveiled the double life of a Yorkshire schoolmaster who served as an undercover agent for Churchill’s ‘secret army’ during the Second World War.

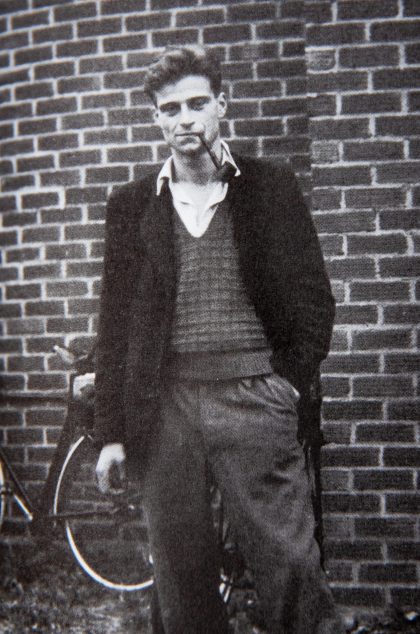

Former Bradford Grammar School (BGS) languages teacher, Harry Rée, told relatives his eight months spent in France, in 1943, had been like a ‘glorious summer holiday,’ where he cycled around and enjoyed people’s hospitality.

But he was actually an agent in Churchill’s Special Operations Executive, known as Churchill’s Secret Army or Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare, where he was tasked with sabotage and subversion behind enemy lines.

Harry was parachuted into France in April 1943, after training in sabotage and silent killing and how to pass yourself off as a native Frenchman. He went on to devise a system for smuggling messages to London, organised dozens of parachute drops and gave instruction in sabotage techniques. He directed operations with the French Resistance against railways, canals, warehouses, electricity supplies and factories.

One of the charismatic teacher’s greatest successes was in persuading Rodolphe Peugeot, the son of the Peugeot factory owner, to sabotage the family premises at Sochaux, which had been commandeered to make parts for Nazi tanks. In return, Harry persuaded the RAF not to carry out another bombing raid on the factory by making a pact to keep up with regular sabotage operations.

Harry’s life as an agent was only discovered by his son Jonathan, an author, historian and philosopher, in 2016 when he was contacted by a French soldier who was keen to track down relatives of the prominent resister.

Jonathan soon found himself on a train to France where, at an impressive civic ceremony to rededicate a memorial plaque, he was astonished to discover his father’s role in the fight against Germany.

Said Jonathan: “He worked directly or indirectly with around 400 supporters, including women and children, not just men, and became extremely close to them. Almost half were arrested at some point, and in many cases imprisoned and tortured, while dozens were executed or deported to camps in Germany from which they were unlikely to return. I can see why he didn’t want to talk about it.”

Jonathan, of Oxford, read dozens of histories and memoirs and looked through piles of family papers. He travelled around France to talk to people who had known Harry and found pages and pages he had written on his return, most of which were either unpublished or anonymous. Slowly, he began to piece together the dangerous reality of his father’s war.

Said Jonathan: “He had actually signed the Peace Pledge at university and was in a reserved occupation as a teacher, but he later reconsidered his position.

“He would have hated to have been portrayed as a hero. He always praised the ordinary unheroic deeds of the men and women of France who enabled him to be part of the Resistance, people who had risked their lives for him.

“He must have been deeply affected by tragedies, such as the death of his devoted assistant Jean Simon, who was gunned down in their favourite café, or the retired schoolmistress Marguerite Barbier, who loved him like a son and died in a concentration camp.”

Harry fled France with stomach wounds after being shot by a German military policeman who had found his safe house. He spent five months recovering from his injuries in Switzerland at the same time as coordinating activities back in Franche-Comte.

After the War, Harry received the Médaille de la Résistance Francaise and Croix de Guerre, and was appointed DSO, OBE and Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur.

He went back to his teaching career, joining BGS in 1949 where he worked until 1951. He later become Professor of Education at York University and retired to an old farmhouse in Ribblehead, in the Yorkshire Dales.

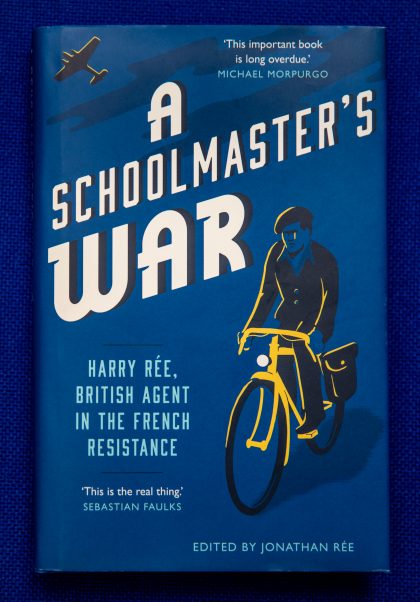

After his extensive research, Jonathan captured his father’s story in a book A Schoolmaster’s War: Harry Rée – A British agent in the French Resistance. He says his father intended to write his autobiography but died in 1991 age 76 before he got the chance.

“I think he would have thought, if there had to be a book, he would have liked it to have been like this one,” he says. “He wanted people to know how ordinary and modest the real heroes of the Resistance were. He never forgot them and never forgave himself for his part in what happened to them. He never ceased to wonder at his absurd good luck at getting out alive.”

“I think he would have thought, if there had to be a book, he would have liked it to have been like this one.”