Big ideas have staying power, and the slow rise of insights from genetics and neuroscience continues to shape educational thought and practice within and beyond Schools. Notions about which individual methods work best in the classroom can however be somewhat ephemeral.

The latest ideas fall in and out of fashion in education, as do their proponents. My co-blogger, Mr Ribeiro, Head of Bradford Grammar Junior School, brings youthful vim and vigour, while I (Old Father Time) remember Piaget’s ‘Cognitive Development’ and Gardener’s ‘Multiple Intelligence’ as the gold standards during my teacher training – now replaced by more recent and enlightened understandings.

Differentiation once dominated classrooms, encouraging teachers to tailor lessons to students’ varied requirements, abilities and learning styles. But this approach often became unwieldy, leading to over-complicated planning and unsustainable (and exhausting!) teacher practice, slowing progress for the majority. Little surprise that differentiation is now less fashionable than it was ten years ago.

As one approach wanes another ascends. Being a self-confessed edu-nerd, I still have a 2015 Guardian clipping heralding the rise of “eastern-inspired ‘mastery’” — a method endorsed by policymakers who even invited Shanghai teachers to the UK to share their approach. The national curriculum for English and maths is now rooted in this philosophy. The reason I hung onto the article was the idea that mastery means creating moments in class where students are in awe of their teacher’s scholarship – moments that spark curiosity and inspire them to strive for that same level of understanding.

Such giddy aspirations!

Awesomeness aside, most teachers will intuitively practise mastery by affording their classes and the individuals within them sufficient time and opportunity for deep learning, rather than accelerating through new material. Time, however, is never in ubiquitous supply. Mastery is not a fleeting trend but a solid, research-backed approach. Even within the fixed structures of UK schooling – with its key stages and academic calendars – mastery has proven its worth. And this is where my co-blogger Mr Ribeiro steps in…

Those of a certain vintage (Dr Hinchliffe included) will recall Mr Miyagi, the mysterious and wise teacher of Daniel in the film franchise The Karate Kid. Just as Mr Miyagi transferred his karate mastery to Daniel LaRusso through deliberate practice (wax on, wax off!), we as teachers aim to help pupils build a firm foundation of knowledge and skills.

The mastery approach to learning prioritises depth of understanding over rote memorisation. It enables learners to acquire a deep, secure and adaptable understanding of the subject, ensuring pupils grasp how and why a concept works, storing knowledge securely in long-term memory so they can apply it in new contexts.

According to the National Centre for Excellence in the Teaching of Mathematics (NCETM) mastery in maths rests on five key principles:

- Coherence – Learning is presented in a logical sequence, helping children build on what they know rather than relying on disconnected tricks and formulas.

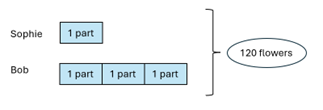

- Representation and Structure – Models, such as bar diagrams, are used to visualise problems, helping pupils ‘see’ the maths, not just ‘do’ it.e.g. Sophie has some flowers. Bob has 3 times as many flowers as Sophie. Together they have 120 flowers. How many flowers does Sophie have?

In this example, pupils can visualise 4 equal parts and can therefore divide 120 by 4 to understand that 1 part represents 30 flowers. Without the aid of the visual model, many students make the mistake of dividing by 3 instead of 4.

- Mathematical Thinking – Pupils are encouraged to look for patterns and relationships, make connections and use reasoning to deepen understanding.

- Fluency – Pupils develop efficient, accurate recall of key number facts and methods, freeing their minds to tackle complex problems.

- Variation – Key features of a mathematical concept or structure are highlighted by varying some elements while keeping others constant.

The Education Endowment Foundation describes the mastery approach as ‘ensur[ing] that all pupils have mastered key concepts before moving on to the next topic’. It involves teachers breaking topics into manageable steps, setting clear objectives and checking understanding through regular assessments. At Bradford Grammar Junior School, maths mastery is embedded from Reception to Year 6. Lessons balance discussion, exploration and problem-solving, helping pupils uncover the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of maths.

We also use the Concrete – Pictorial – Abstract (CPA) approach, where pupils explore new maths concepts in a concrete way using real-life situations and objects and use mathematical representations to help them make sense of abstract concepts.

The mastery approach is also well-suited for the Early Years classroom, as young children are naturally curious about the world around them. In early maths education, it is crucial for children to grasp the fundamental concepts of mathematics. Some may start school already able to count to 10 and beyond, but do they truly understand the meaning behind these numbers? To deepen their understanding, children are encouraged to represent numbers in various ways, using real-life objects, mathematical tools, drawings, sounds and movement.

Further along the Junior School journey we want our learners to move from memorising formulas to understanding why they work – for instance, why the area of a triangle is calculated as 1/2 base x height.

We have made significant efforts to align the maths curricula and teaching approaches between the Junior and Senior Schools. Leaders from both schools meet regularly to ensure a smooth transition, allowing Year 6 pupils to carry their secure, adaptable knowledge into Year 7 with confidence.

And, as Mr Miyagi said, “If the root is strong, the tree will prosper.”

“We as teachers aim to help pupils build a firm foundation of knowledge and skills.”