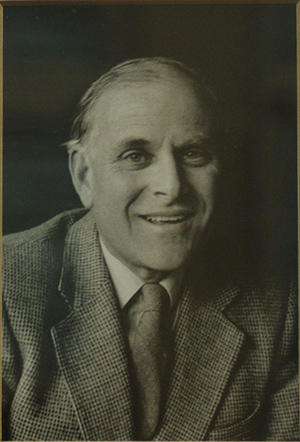

Raymond Shaw-Smith, Classics Master, 1952-89

A Memoir

Room 27 at BGS from 1952-89 will have special significance for generations of classicists at BGS. It was the room occupied by Raymond Shaw-Smith, a Classics Master much admired and loved by those who had the good fortune to be taught by him. My own memories span the years 1954-62 and subsequently in his later years in retirement from 2008 onwards, while I was writing ‘Haec Egimus’.

I first encountered Raymond properly in 1956 when he was our form master in TC (year 9) and teacher of Greek, but his reputation had run before him. His room was directly opposite the spot where pupils used to form an often unruly queue for school dinners, with the inevitable consequences as they jockeyed for position! Often the door of room 27 would swing open and a young Master of commanding demeanour and authoritative voice would emerge. An incipient riot promptly quelled! Here was a teacher who could stamp his authority and would brook no nonsense. We had been warned.

Of course, we quickly realised that Raymond Shaw-Smith was far more than that. We all soon came to appreciate his outstanding qualities as a teacher, by turns conventional and unconventional. Learning was fun, it was never boring: Raymond exuded life, and he knew how to motivate able pupils: verve and imagination in his approach, bonus marks for accurate learning, intolerance of arrogance. Classics still held a premier position in the curriculum and the department was strong – all members were Oxbridge classicists – but Raymond was the young Turk, the breath of fresh air that it needed.

Raymond’s appointment in 1952 by R B Graham proved to be a far-sighted one. The Classics Department was strong with highly qualified, experienced teachers: Raymond was to be the junior member, the post having been filled in quick succession by two appointees who had both quickly departed. Raymond was to give 37 years’ devoted service.

Raymond, we later discovered, was an accomplished scholar of University College Oxford, a versifier par excellence and a winner of the Chancellor’s Medal: it’s worth remembering that in those days classicists had to produce not only Latin and Greek proses but verses too of reasonable competence. No one could rival Raymond’s facility, but his example was inspirational: my close friend, Chris Kelk, now a professional actor in Toronto, has spent an enormous amount of time translating Latin and Greek poetry, and, right until the end of Raymond’s life, Chris used to send him specimens of his latest work for comment. He was a mentor for both of us – for Chris and his verse, and for me as I laboured over my own magnum opus: his comments simultaneously to the point, encouraging and often entertaining. My suspicion is that while at University he concentrated on those things which enthused him. Many years later in conversation he recalled part of his own viva voce exam for Greats, which included the following:

“Now, Mr Shaw-Smith, shall we talk about Aristotle?”

“No!” replied Raymond defiantly, “I don’t want to talk about Aristotle!”

Stunned silence…

Raymond and I chuckled in remembrance.

As youngsters in 1956, we all wondered what was in store for us. We had in a strange sort of way got some inkling of his independent spirit – even irreverence – because he had set the Greek exam at the end of the previous year. And it was an exam with a difference. There was no solemnity in the sentences we were set to translate: none of ‘the armies faced each other across the battlefield’. Instead his sentences resonated of ‘The Goon Show’, the cult comedy of the time. The vocabulary we had learned during the course of the year was tested in such gems as ‘the arrow flew out of the eagle’s head’. Titters soon broke out around the exam room and Eric Ewbank allowed a knowing smile to cross his face! The concluding question is engraved in my memory: ‘Using your knowledge of Nursery Rhymes what is “to zoon oon”? Literally translated this means “the animal egg”, and after a few seconds most of us worked out the correct answer: Humpty Dumpty! The whole exam was a light-hearted dig at the orthodoxy of the traditional text books. We loved it! Raymond, we soon discovered, had a natural presence in the classroom which was a place for learning, but there was always life and fun in abundance, not to mention moments of unintended pantomime drama.

I recall, as I’m sure other classicists of my year should do, an occasion when we were reading an elementary Greek reader. Invariably in a new foreign language, whether it’s Ancient Greek or German, you hear sounds which suggest rude or slang equivalents in English. The word ‘heistias’ which means ‘you are feasting’ appeared in the text. All language teachers face the problem of quelling adolescent sniggers. Raymond’s solution was instinctive and immediate. “Ok,” he said, “now have a good laugh and get it out of your system!” Simultaneously he wrote the offending word in English in his impeccable Italic script on the blackboard.

We did, with a gusto, at which point there was a knock on the door and in walked the Headmaster. An embarrassed silence. Eyes down. Suppressed giggles. Raymond made no attempt to conceal the wording on the board, and fortunately the Headmaster did not look in that direction. He beckoned Raymond outside the classroom to discuss something unconnected – I believe – with the laughter he must have heard. He returned a few moments later, and there was immediately a knowing look exchanged between him and us, a moment of empathy. Relief for him and for us. A bond had been forged.

Many years later Raymond (who had no recollection of the event I’ve just described) told me that as a young teacher he used to send the Headmaster, relatively newly appointed, notes/suggestions. I have no idea what they contained (though I’d have loved to know), but I strongly suspect that the ideas in them would have been rather too unconventional for the Rev J P Newell! Raymond told me of an occasion when the Headmaster had knocked on his door while he was teaching to tell him ‘I will have no more of these notes!’ That, I believe, was the purpose of the Headmaster’s visit.

Raymond was a man of strong, sometimes anti-establishment, views. While researching my book, which Raymond kindly proof-read, I spent one nostalgic and happy afternoon skimming the pages of the Masters’ minute books for the period 1949-63. Among the often mundane but detailed minutes I came across an occasion when Raymond protested about compulsory cricket, when, for significant periods, pupils on the batting side were left unoccupied and inevitably got up to mischief – a headache for the master in charge. He suggested its abolition! The Second Master, Willy Ed Clarkson, who was chairing the meeting (so Raymond recalled) looked pained, but the motion was carried by a huge majority. He had raised his head above the parapet and touched a nerve, though nothing, of course, changed. The story subsequently became embellished in the Common Room. One former colleague, the late Dennis Ward, told me that R had made the suggestion that the two teams should represent opposing Roman armies and do battle with each other on the field! A story Raymond strongly denied!

In the mid/late 1950s, a group of senior pupils, spearheaded by the late Bill Speck, wished to start a Jazz Club; any club needed the support and supervision of a member of staff. Jazz (along with most modern music) was the type violently opposed by the head of Music, Leslie Walsh, who would not allow it to be heard in the Music Room. Raymond, however, agreed to supervise it as he felt the pupils had made a perfectly reasonable request: he used to sit silently marking his books at the back of room 27 while the pupils organised the sessions. He admitted to me that he did not particularly like the music himself, but felt the Club should go ahead, and it went ahead under his ‘light-touch’ supervision.

Independence and originality infused his lessons: something as potentially tedious as the declension of ‘hic haec hoc’ became a lively game when a wrong answer could lead to a pupil being locked in the store room cupboard! His colleague Robert West recalled the story in his splendid tribute to Raymond on his retirement in ‘The Bradfordian’ of 1989. In his teaching of Ancient History, Raymond was insistent that as sixth formers we should be able to make reference to original source material rather than second hand text book histories: we should search out original evidence and weigh its significance. He had us diving into Suetonius’s ‘Lives of the Caesars, Tacitus, The Res Gestae‘ of Augustus and introduced us to Roman inscriptions, when we were studying the Julio-Claudian period. There was to be no uncritical regurgitation of the standard history book. It was important initial training for any aspiring historian.

Raymond was a committed and enthusiastic Classicist in every sense, even helping his colleague, Donald Haigh, to decipher some Latin inscription above the entrance doorway to Thornville, the Junior School. His walks along the Roman Wall are well recounted in ‘The Bradfordians’ of the 50s; he produced Aristophanes’ ‘Acharnians’ in the original Greek, using members of sixth Classical as the cast, with a great performance from the late Pete Medway in the lead role; he delivered a funeral oration in Latin in memory of the Emperor Tiberius from the elevated position of the Masters’ car park to his audience of sixth form Classicists, as we listened attentively on the front field. Stuart Parkes recalls that he sometimes donned his raincoat to protect himself from chalk dust! His mnemonic devices stuck in the memory: ‘mens and gens are feminine because they are hens, pons and mons are masculine because they are dons’. Stuart adds: ‘His method was to make things real.’ He was a late convert to Shakespeare: an early bad experience as a pupil of a performance of Antony and Cleopatra in Liverpool had kept the great bard at bay for many years: one wag in the audience as Cleopatra applied the asp to her breast had called out “Atta, girl!” He acted as prompt for the Shakespearean productions of the 50s and became a convert to the language. It led him to produce Antony and Cleopatra himself. He also was a keen supporter of the musical life of the school both in the choir and orchestra.

He loved the outdoors and was a keen attender of the school camps at Drebley on the banks of the Wharfe near Appletreewick; he shared in the camaraderie, his tenor voice clearly audible around the camp fires, or entertaining the group with his experiences of learning to drive! He was later to write a memorable poem entitled ‘Those Drebley Days’ for the OBA Annual Dinner. Its opening verse goes as follows (the references in line three are to Bill Smith and Eric Ewbank, the founding members of the camps):

Two miles downstream from Burnsall

And two above the Strid

White Arrow and Tree Creeper

Invested fifty quid:

Guarded by fir plantations

Now tall that then were dwarf

They made a golden acre

Of Bradford by the Wharfe.

Raymond was also a no-nonsense disciplinarian when the situation arose. He would speak his mind and his rare shows of anger always hit the mark. Pupils listened and took note. My friend Mark Ashley recounts an occasion when, during lunch break, some horseplay was going on in room 27 which involved the use of the window pole. Alas, the intended objective was missed and the window pole went straight through the window. Mark duly confessed his guilt to Raymond, whose withering words are instilled in his memory to this day:

“Ashley, you are a complete idiot! Now begone!”

His classical training had made him a master of English prose and he was often called upon to write portraits of retiring colleagues – those on F L ‘Charlie’ Somers and R E F Green are fine examples. His words were felicitous, never wasted, and his eye for detail acute. Consider this snapshot of Charlie Somers:

‘His colleagues knew him as a meticulous teacher with a demanding attention to responsibilities, his own and other people’s. He never actually knocked his pipe out on our heads, but he was often seen reviewing his seemingly illegible agenda on a scrap of paper in a haze of smoke, and once you were an item on that agenda you did not easily escape.’

Likewise his comments on essays were eagerly awaited and his judgements on reports pithily witty: ‘If I work hard he will pass’ springs into my mind!

During the academic year 1960-61 he took the then unusual step of taking a year’s sabbatical of unpaid leave, with the Headmaster’s blessing. We missed him badly as his inexperienced young replacement had none of Raymond’s presence or panache. The magazine regularly charted his travels across continents, even visiting Borneo. On his return he gave a vivid account of his journey to the whole sixth form. And it was then revealed that he had become engaged to his wonderful future wife, Dolores.

Raymond and Dolores were to raise their family of four boys (all of whom attended BGS and won places at Oxbridge Colleges) on a remote farm house on Harden Moor. When Raymond purchased the farm in the early 60s much work on renovation and modernisation was needed. Pupils and former pupils were regularly and willingly recruited to help with various tasks. I recall that my late friend Graham Bradshaw and I visited to help clean out a pigsty. Happy days!

They say that great teachers inspire: Raymond was a shining example. Those of us fortunate enough to be taught by him could never understand why he was overlooked as a head of department. He was modest to a fault. My friend Chris Kelk and I maintained regular contact with him, and he was a frequent attender of gatherings of the 1950s classicists’ reunions, travelling long distances well into his 80s. Chris and I both toasted his memory from afar on the day of his funeral – Chris from Toronto, I from Melbourne. We will miss him but we will always cherish his memory.

David Moore, 1952-62.

_____________________

With deep regret BGS announces the passing of Old Bradfordian (OB) Mr Raymond Shaw-Smith (Taught at BGS 1952-1989)

Mr Shaw-Smith came to BGS in January 1952 on a temporary appointment just for a term or two. Hardly any BGS staff have exceeded the 37½ years of service he then proceeded to give. It is arguable that none has equalled the range of his contribution – on the games field in earlier years (though not always fully changed), more latterly as CCF Naval Officer and sailing instructor; as a producer of School plays, and star of a prize-winning School film; making music in the choir and writing poetry for the Old Boys’ dinner menu; teaching a variety of subjects, such as AO level Navigation, which would have been unlikely to find their way into Mr Baker’s National Curriculum; and above all as a teacher of Woodwork, who had remarked about a colleague that whereas others had taught the classics, this man had actually read them.

Admiration, affection and a thorough knowledge of classical literature informed Mr Shaw-Smith’s writing and conversation, as well as his teaching. He was a regular contributor of an English poem to Yorkshire Life (generally with an accompanying photograph by Mr Smithson). When colleagues retired, as often as not it was he to whom the editor of ‘The Bradfordian’ turned for what he knew would be a felicitous and fair memoir. His sometimes sharp but always pertinent comments made at staff meetings, in lessons or on reports were remembered and often savoured for years afterwards (“he will pass if I work very hard”, he wrote on one boy; on another, somewhat enigmatically, “I have not seen him since he lost his book”).

Having received a classical education in its full rigour at the Liverpool Institute and at University College, Oxford, he was well qualified, as the golden age of Classics teaching approached its final lustrum, to have that appointment made permanent and hand on what he had received. However, essentials and their elegant presentation mattered to him more than erudition and dull exactitude; the teaching of Classics had become a faster, more streamlined business over the years, but pupils left him with the same sound grasp as ever and continued to achieve astoundingly good results. Those who discontinued even at an earlier stage came away in no doubt of what was involved in the learning of Latin. Those who persevered with Classics into the Sixth Form shared the insights of a scholar whose article on textual uncertainties in Tacitus was published in a learned periodical; and learned how to compose Greek and Latin verse under a teacher who won the Chancellor’s Medal for Latin verse at Oxford.

Mr Shaw-Smith was concerned to present Classics as an approachable field of study, not at all remote or esoteric, provided you do the work and not overreach yourself. His scorn was directed chiefly against those, young or old, who did not, in his view, understand what they were dealing with; nor did he keep his feelings to himself, as many an editor of a newspaper or classical journal will testify. Nevertheless, with those who would reason, he would reason back; he saw Classics not as a vehicle for intellectual snobbery, but as a civilising influence, which asserts (as he wrote in a fine defence of Classics published in the Sunday Telegraph) that “discourse is to be superior to a punch on the nose”.

With a clear idea of what he was here to do, and with no diminution in the brisk energy which so impressed the staff he joined in 1952, he guided generations of pupils through the main streams and the byways of classical literature and history. He also eased from them the sheer tedium of learning Latin grammar; “grammar grinding” can never have been so hilarious as in Room 27, and few pupils who met it there will ever forget the declension of hie, haec, hoc. Whenever I attended classics gatherings around the country I generally meet someone who did his Classics at BGS, and invariably it is Raymond Shaw-Smith whose lessons these people remember most vividly and with most affection and gratitude.

Adapted from an article written by Robert West in ‘The Bradfordian’ on Mr Shaw-Smith’s retirement.

“Admiration, affection and a thorough knowledge of Classical literature informed Mr Shaw-Smith’s writing and conversation as well as his teaching”